“The white dean of my school kept introducing me as the 16-year-old freshman from West Africa who’d already read Dickens and Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, as if any of that was surprising or special,” they write. at 16, having read everyone from Chinua Achebe to Daphne du Maurier, Emezi was treated as exceptional by white folks. “While the town was burning from the riots,” they write in Dear Senthuran about life under military dictatorship in the ’90s, “my sister and I believed in invisible fairies, pixies hiding in our backyard.” They credit such an appetite to the piles of books they had access to, some purchased secondhand at the local post office, some shipped from cousins in London and others found on their parents’ bookshelves.

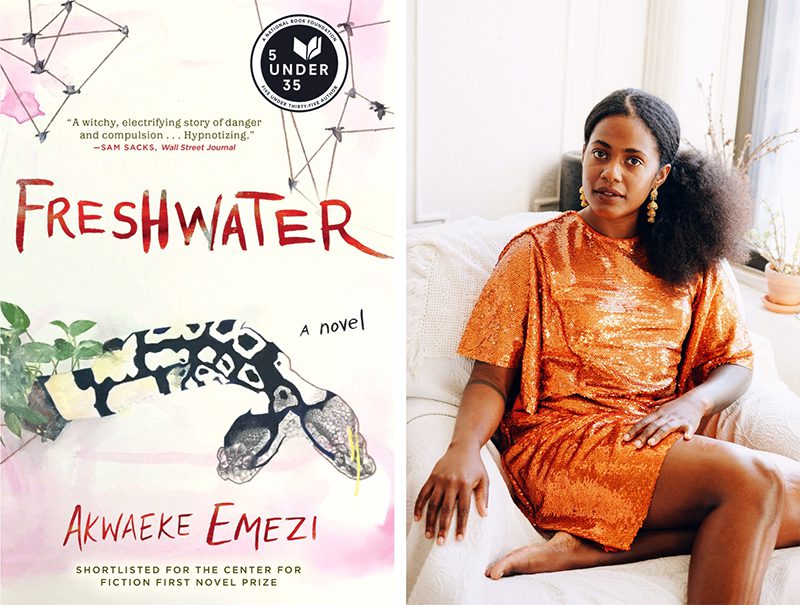

Growing up in Aba, a commercial town in the south of Nigeria, they were a voracious reader and writer from an early age. “I’m going to write this as if it’s just us,” they recall telling themself about the memoir, “because in my reality, in my world and in a world where we are free, it is just us.”Įmezi, who turns 34 on June 6, has been world-building since childhood. The viscerally intimate chronicling of Emezi’s lived experience, out June 8, serves as a manifesto marking a shift in their career away from the all-consuming white gaze toward a perspective that is Blacker and more beautiful. That’s where their latest book, Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir, comes in. “I understand all the limitations that are put on us just by existing in this world, by trying to create work in this world, and I’m saying: To hell with that.” As a Black author who’s always expressly desired to write for Black people, they’re at a moment in their career where being their most unapologetic and authentic self is not only possible, but also paramount. “Just to be able to talk to my own people is freedom,” Emezi says on a recent morning via Zoom, describing the ways writing for white audiences, or rather a publishing industry that centers white readers, is the exact opposite.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)